Do you think excellence and the success achieved by it is a gift, randomly luckily genetically bestowed or is it earned by effort? Matthew Syed, sports star, prizewinning Oxford student, leading Times commentator and features editor, bestselling author (summary: over-achiever extraordinaire) has a lot to say about this, and it is well worth hearing. I’m going to try to explain some of his main theories, discuss my thoughts on them and lastly discuss how we might apply them into our lives or the lives of our children to help them achieve their potential. I hasten to add, my poor summary is not an excuse not to read these brilliant books, which are insightful page-turners stuffed full of relevant and interesting case studies across a broad range of personalities and industries.

Outliers and Bounce: The myth of talent and the power of practice

I’m sure many of you will have read the bestsellers, Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and Syed’s Bounce. In case you haven’t, in a nutshell: Gladwell shows how the success of many outstanding “outliers” from the Beatles to Bill Gates, were “invariably the beneficiaries of hidden advantages and extraordinary opportunities that allow(ed) them to work hard and make sense of the world in the ways others (could) not”.  That is not to deny the role of special talents, but rather to say that they are not unique – many others would have similar talents which without the unusual circumstances or opportunities stacked in their favour, would not triumph to absolute potential and operate at the extreme outer edge of what is statistically plausible. Bounce: The myth of talent and the power of practice develops this further. Syed illustrates how, in any complex field whether it be firefighting, chess, violin playing, football or table tennis, expertise is entirely dependent upon long experience of a certain kind. Both Outliers and Bounce discuss a 10,000 hour rule: it takes at least 10,000 hours of purposeful dedicated practice to make an expert. By purposeful, he means targeted and effective: “Mere experience, if it is not matched by deep concentration, does not translate into excellence”. So you need to stick at something for long enough with the right attitude. Purposeful practice was the “only factor distinguishing the best from the rest”. What about child prodigies? Well, Syed states, Tiger Woods and Mozart just started intensive practice much earlier than everyone else.

That is not to deny the role of special talents, but rather to say that they are not unique – many others would have similar talents which without the unusual circumstances or opportunities stacked in their favour, would not triumph to absolute potential and operate at the extreme outer edge of what is statistically plausible. Bounce: The myth of talent and the power of practice develops this further. Syed illustrates how, in any complex field whether it be firefighting, chess, violin playing, football or table tennis, expertise is entirely dependent upon long experience of a certain kind. Both Outliers and Bounce discuss a 10,000 hour rule: it takes at least 10,000 hours of purposeful dedicated practice to make an expert. By purposeful, he means targeted and effective: “Mere experience, if it is not matched by deep concentration, does not translate into excellence”. So you need to stick at something for long enough with the right attitude. Purposeful practice was the “only factor distinguishing the best from the rest”. What about child prodigies? Well, Syed states, Tiger Woods and Mozart just started intensive practice much earlier than everyone else.

Seriously? The genes theory to me was pretty entrenched before I read these books. Watching any sports star or musician, it is very difficult not to believe they are just born with unique talents in their genetic code. As Syed states in Bounce: “the very idea that we could achieve similar results with the same opportunities seems nothing less than ridiculous”. We couldn’t obviously, without a certain level of talent (those of us who are born relatively tone deaf could never be Mozart). But beyond that, within the talented, those who triumph excel by virtue of hard work and attitude. Syed also shows how accepting the practice theory is deeply advantageous psychologically and societally. If you believe that success is all the result of a natural talent with which you were not bestowed, why bother working hard? Since you think you will never be any good anyway, any effort you might put in is futile. A self-fulfilling prophesy if ever there was one. Syed talks in Bounce about the talent theory being not only “flawed in theory” but “insidious in practice, robbing individuals and institutions of the motivation to change themselves and society”.

As Syed states in Bounce: “the very idea that we could achieve similar results with the same opportunities seems nothing less than ridiculous”. We couldn’t obviously, without a certain level of talent (those of us who are born relatively tone deaf could never be Mozart). But beyond that, within the talented, those who triumph excel by virtue of hard work and attitude. Syed also shows how accepting the practice theory is deeply advantageous psychologically and societally. If you believe that success is all the result of a natural talent with which you were not bestowed, why bother working hard? Since you think you will never be any good anyway, any effort you might put in is futile. A self-fulfilling prophesy if ever there was one. Syed talks in Bounce about the talent theory being not only “flawed in theory” but “insidious in practice, robbing individuals and institutions of the motivation to change themselves and society”.

Black Box Thinking: how a growth culture turns failures into success

Black Box Thinking is really about failure, or more accurately, how we learn from failure both as individuals and on an industrial, professional or global scale. Syed shows how in various contexts or industries, creative inventions, scientific breakthroughs, entrepreneurial success or sporting triumph result from a particular way of thinking which embraces failures and systematically integrates the lessons learnt from them. From sport to business, politics to healthcare, aviation to innovation, Syed explains the transformative effect of a positive attitude to failure. Henry Ford bankrupted a few companies before his success story, but his “growth mindset” that allowed him to learn from the errors and innovate further was the key to his entrepreneurship. If we create a culture of shame around failure, mistakes may not even be sought or acknowledged, let alone learnt from such that we advance and improve. Syed’s discussion of the aviation industry (blameless black box thinking with a relentless commitment to continual improvement – where did we go wrong and how can we stop that happening again) vs medical profession (culture of pre-emptive individual blame before even addressing the facts, back-covering and defensiveness the norm) is fascinating. Message from Black Box Thinking: The secret to success, on any scale, relies on the development of a “growth mindset” which sees failures as an opportunity for improvement rather than a “fixed mindset” which feels threatened by challenges and is deterred by failures. As is instantly apparent, the benefits of a growth mindset lead not only to psychological and individual success but to cultural change, a kinder society and industrial advancement.

Henry Ford bankrupted a few companies before his success story, but his “growth mindset” that allowed him to learn from the errors and innovate further was the key to his entrepreneurship. If we create a culture of shame around failure, mistakes may not even be sought or acknowledged, let alone learnt from such that we advance and improve. Syed’s discussion of the aviation industry (blameless black box thinking with a relentless commitment to continual improvement – where did we go wrong and how can we stop that happening again) vs medical profession (culture of pre-emptive individual blame before even addressing the facts, back-covering and defensiveness the norm) is fascinating. Message from Black Box Thinking: The secret to success, on any scale, relies on the development of a “growth mindset” which sees failures as an opportunity for improvement rather than a “fixed mindset” which feels threatened by challenges and is deterred by failures. As is instantly apparent, the benefits of a growth mindset lead not only to psychological and individual success but to cultural change, a kinder society and industrial advancement.

What do I think of the talent vs hard work debate and black box thinking?

Skip this section if you are in a hurry – it is just my opinion and own experience!

I wholeheartedly agree with Syed’s theories. I think there are some areas/professions/industries where it is more applicable than others, and like all good stories/theories/books, some data is perhaps cherry picked, but the generalisation is an accurate one and a deeply motivational positive one.

There is one (irrelevant) context in which I was one of the outlying super-achievers, which is in academics. I have an academic record described by Harvard as spectacular and outstanding, by King’s College as the best student in living memory with a complete set of straight firsts that superlatives do not exist adequately to describe and is still unmatched 15 years on. I’ve heard the whole genetic lottery thing many times. It doesn’t annoy me at all and I would happily perpetuate the illusion that I was just born effortlessly academically gifted, but it just isn’t true. I was always intellectual and quick-minded. My earliest memories include teaching myself to read and frustration in classrooms with teaching methods that couldn’t keep up (I had been in 5 schools by the age of 7, and by 10 was on a continuation scholarship to a future school as well as an existing scholarship). My parents have multiple stories about how inquisitive and slightly challenging I was from a very young age. However, I fall one hundred percent within Syed’s theories on the myth of talent, the myth of meritocracy and the myth of child prodigies. My academic record is attributable to hard work, a particular attitude and a unique set of circumstances, not any innate ability or talent and I can explain it in exactly the same way he explains his own story and those of his case studies.

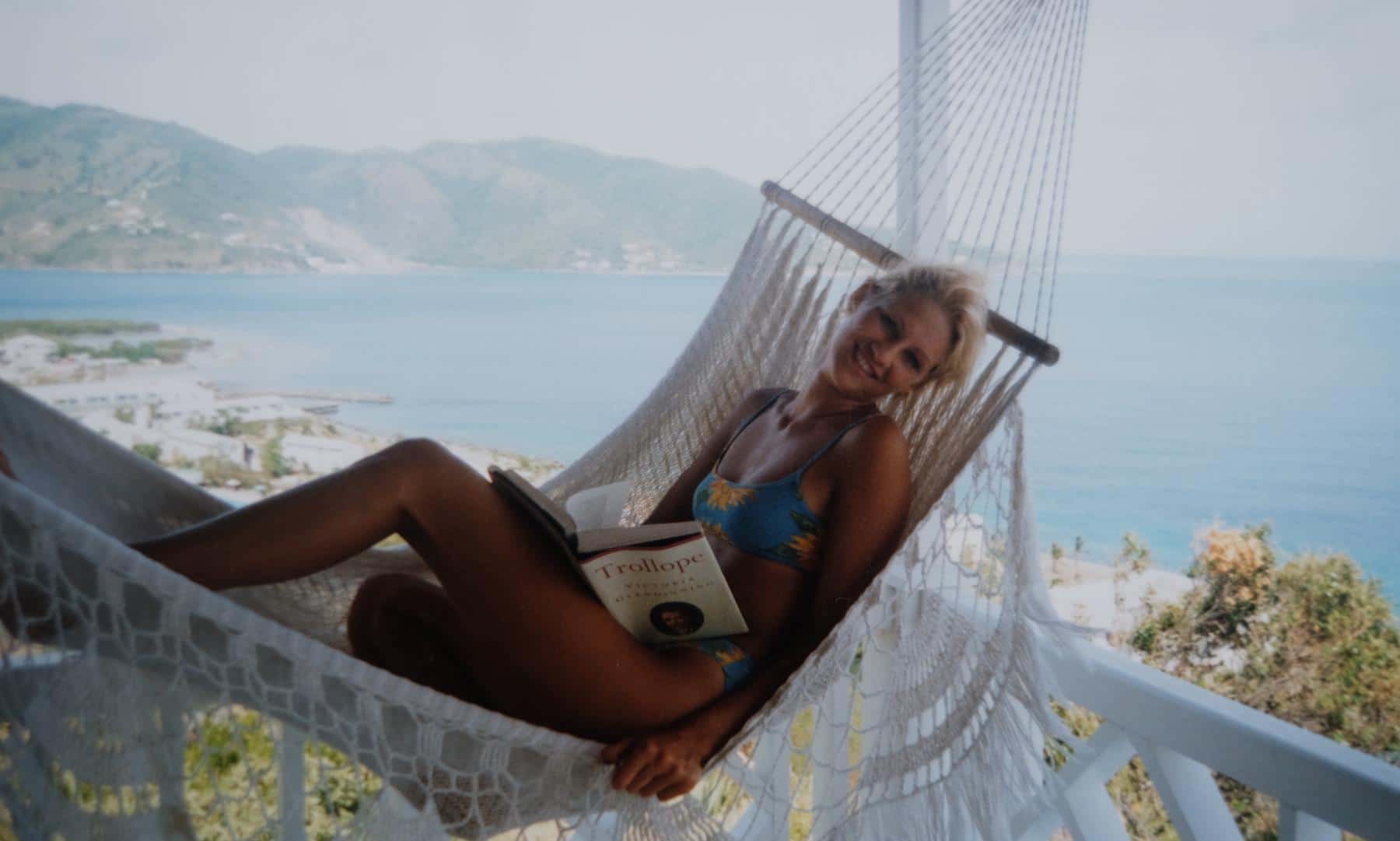

Taking circumstances first, I grew up abroad as a diplomatic child, and my father was in head of mission positions by the time I was 10, in small mainly Caribbean countries for which he became known as an expert. We didn’t have any television channels worth watching, the internet and tablets didn’t exist, our school friends were thousands of miles away, both my parents worked and we had no normal life domestic tasks like shopping, cooking or laundry because it was all done by staff. So during school holidays, there was often very little to do other than read. Other than attending/hosting official functions, doing occasional courses in watersports, visiting Mayan ruins or cultural places of interest, short beach or rainforest trips, my life was about reading. I suspect I had easily clocked up 10,000 hours of reading by the time I started law school, so I was very quick at it, at least in comparison to the average student. To describe my parents’ book collection adequately is a task I am completely incapable of, but in terms of both quality and quantity, it is probably as impressive as many libraries in certain genres. This brings me on to the attitude point. I read a lot of biographies. My father read biographies and, ever keen to please him (I worshipped him) and have something to discuss with him over dinner and evening card games, so did I. You can see me here reading a biography of Trollope aged around 14 or 15 in BVI where he was Governor. By definition, those who write biographies are successful, impressive and hardworking. These were the people whose life stories I knew; these were my role models. We also had fairly constant adult company and very little peer company. It was perfectly normal for my sister and me to be having lunch or dinner with a group of officials almost every day in school holidays. We had to talk properly and make adult conversation about current affairs or tourism or education etc. much more than most young people. We heard endless speeches from the opening of new buildings, hospitals or schools to tree-planting ceremonies, all of which meant listening to far more motivational talk than the average teen. Lastly, but not least, more than anything, I was born with a huge capacity for concentration and hard work and an innate internal drive that came from nowhere.  My personal tutor at University who got to know me well said “Shona’s vivacious upbeat personality, sense of fun and aesthetic belies her seemingly limitless capacity for sheer hard work and commitment to whatever she puts her mind to”. I studied very hard. I have a mind that is capable of ignoring even serious pain where it gets in the way of work and I am in a state referred to by psychologists as “flow”. One of many examples: I once temporarily totally crippled myself to a neurologist’s total disbelief until they stuck electrodes on my totally dead lower leg nerves and looked at my mother saying, “this is impossible – she wasn’t asleep or intoxicated? I had been kneeling drawing charts to memorise facts for the New York Bar exams (as a child/young adult, I had a mildly eidetic or photographic memory so charts and graphs helped me learn). I read not only every reading list and further reading list but articles or case law referred to in further reading lists that sounded interesting. I sat at the front in class. I asked questions and spoke to tutors afterwards if something was unclear. I loved work and always will – this never felt like a chore. My mind is just curious and I have an obsessive desire for knowledge and learning. I also had a sense of opportunity cost that other students may not have felt because I had given up modelling (lucrative) to study. Syed talks about attitude and psychology a lot in both Bounce and Black Box Thinking and I fit in to all his theories. I always believed in my abilities, but I never believed myself better than anyone else in any context. I believed in my ability to work hard to achieve my potential. I never slacked off. I always thought I could improve and do better. Even after exams where I had achieved the highest ever grade, I would mentally de-brief myself on all the points that I had missed. It all makes me sound very odd as a student or young person but I had a lot of fun in summer holidays and it just worked for me to study very intensively during the academic year. I enjoyed it, and putting my all into everything was just the only way I knew how to exist. I know my children are highly unlikely to have these characteristics – their lives are just too normal. My childhood was very unusual, and while I hope they achieve their potential academically, working as hard as I did is in hindsight fairly pointless, though it did of course make job interviews a formality. Some of my job interviews were nothing short of hilarious – top of page: hired but just check she isn’t a total weirdo but even if she is we could put her in a PSL role. (Professional Support Lawyers are the really geeky ones who update template documents and keep the firm up to date on new case law and other legal developments. They don’t see clients).

My personal tutor at University who got to know me well said “Shona’s vivacious upbeat personality, sense of fun and aesthetic belies her seemingly limitless capacity for sheer hard work and commitment to whatever she puts her mind to”. I studied very hard. I have a mind that is capable of ignoring even serious pain where it gets in the way of work and I am in a state referred to by psychologists as “flow”. One of many examples: I once temporarily totally crippled myself to a neurologist’s total disbelief until they stuck electrodes on my totally dead lower leg nerves and looked at my mother saying, “this is impossible – she wasn’t asleep or intoxicated? I had been kneeling drawing charts to memorise facts for the New York Bar exams (as a child/young adult, I had a mildly eidetic or photographic memory so charts and graphs helped me learn). I read not only every reading list and further reading list but articles or case law referred to in further reading lists that sounded interesting. I sat at the front in class. I asked questions and spoke to tutors afterwards if something was unclear. I loved work and always will – this never felt like a chore. My mind is just curious and I have an obsessive desire for knowledge and learning. I also had a sense of opportunity cost that other students may not have felt because I had given up modelling (lucrative) to study. Syed talks about attitude and psychology a lot in both Bounce and Black Box Thinking and I fit in to all his theories. I always believed in my abilities, but I never believed myself better than anyone else in any context. I believed in my ability to work hard to achieve my potential. I never slacked off. I always thought I could improve and do better. Even after exams where I had achieved the highest ever grade, I would mentally de-brief myself on all the points that I had missed. It all makes me sound very odd as a student or young person but I had a lot of fun in summer holidays and it just worked for me to study very intensively during the academic year. I enjoyed it, and putting my all into everything was just the only way I knew how to exist. I know my children are highly unlikely to have these characteristics – their lives are just too normal. My childhood was very unusual, and while I hope they achieve their potential academically, working as hard as I did is in hindsight fairly pointless, though it did of course make job interviews a formality. Some of my job interviews were nothing short of hilarious – top of page: hired but just check she isn’t a total weirdo but even if she is we could put her in a PSL role. (Professional Support Lawyers are the really geeky ones who update template documents and keep the firm up to date on new case law and other legal developments. They don’t see clients).

How can Syed’s theories from Bounce and Black Box Thinking inform how we parent our own children? What can we do to help them achieve success?

I have tried for ease of reading to split these into headings, but they are not mutually exclusive and many of these points are closely linked and could all be subsumed under a single heading of “growth mindset for marginal gains”, though until you’ve read Black Box Thinking, that won’t mean very much to you!

1. Positive thinking

Positive thinking is extremely effective in life (and in sport – there’s obviously a lot about sport in Syed’s writing; Bounce in particular). A belief in your own ability to perform is vital for success. Even if/when totally illogical by reason or fact, a player must believe he can win if he is to win. It doesn’t matter where this belief comes from (religion, superstition, born with it, a placebo drug), it just must be there. If you’re interested in this, read the second section of Bounce: Paradoxes of the Mind. So tell your children they CAN DO IT. Foster a healthy confidence that they believe in themselves and their ability to triumph via commitment and hard work. (Just don’t tell them they are intelligent – see below at 5.)

2. Purposeful dedicated practice

Practice develops an activity-specific knowledge base that leads to activity specific performance improvements. Allowing children to believe in the incorrect assumption that success is an effortless, easy or instant phenomenon will hold them back. Tell your boys about David Beckham. I have five 8 year old boys this weekend for a sleepover party and their bedtime story will be Black Box Thinking: Chapter 13 The Beckham Effect. Anyone at the top of their game looks effortless in the performance of their skill. But that is because of all the hours of practice they have put in; not just from some innate talent or superiority.

3. Resilience, feedback and the growth attitude that allows failure to turn into success

Failure is one of the keys to success. You must be able to fall again and again and get back up. Doing things wrongly, and more importantly learning how to do things correctly from doing things wrongly the first time is a crucial part of improvement and learned excellence. Do not have a culture of blame in your children’s lives. Foster a growth culture that embraces failure and teaches strategies to learn from them. Syed talks about “leveraging opportunities” into “marginal gains” – doing things wrongly or failing in any sense of the word allows you to learn from it. Teach your kids that the only true failure lies in not even trying. Trying + failing = higher likelihood of success next time. Look to learn and show how to take rational risks. Encourage them to ask questions all the time and answer them patiently. Never ever make them feel that asking questions is stupid or shows a lack of knowledge. There is always room for improvement: no one knows everything and humility is an essential part of the growth mindset. Foster an open growth mindset any way you can.

4. Feedback

Giving feedback is crucially necessary for improvement. It helps correct and fine tune skills. This is part of the growth mindset fostered by an environment where all participants work together to allow for marginal gains. Go through marked work or debrief sports games with your children. What went wrong there? Why? How could you have stopped that happening? Take time to discuss tactics in board games. Be honest about your own failures and show how you learnt from them. I do this on a micro scale all the time with no sense of shame, e.g. “oh Mummy has burnt flapjacks! Look guys!.. Mummy should have..” Create a marginal gains culture in your home. E.g. “Right guys, we are late on the school run AGAIN. This is our plan. 1. Mummy’s alarm 5 mins earlier, 2. All school kit and book bags ready the night before.. etc.”

5. Praise effort/practice not intelligence/talent

Telling children that they are intelligent is not good for them. They perform worse. Read Carol Dweck’s research on this if you doubt me! Fascinating. In a nutshell, if you encourage your child to think of himself as intelligent from an early age, there is a strong chance they stop trying hard and slack off. In comparison, if you consistently show the link to your children between hard work and achievement, your child will want to work harder. The correct vocabulary aligns the young mind with the qualities they need to develop in order to achieve their potential. Praise them for their effort, dedication, hard work, resilience, ability to learn from mistakes, improvement. Descriptively praise these qualities such that they become ingrained in your children and they know how to repeat the behaviour. Praise the behaviour, characteristics and qualities you want to see more of – seeking parental approval is a powerful motivator on children. The Tiger Woods stories Syed discusses are fascinating on this point. (His books are well indexed, so you can look up discussions of individuals you might be particularly interested in).

6. Make school year adjustments if necessary

If you have summer babies, consider holding them back a year at some stage in their education IF they look like they aren’t keeping up. Gladwell’s Outliers’ description of the ice hockey players in Canada is thought provoking. In a nutshell, all the national players were born in the first few months of the academic year. Gladwell’s theory for this: older kids are bigger and stronger, which coaches would mistake as better, faster, stronger, more coordinated, more talented. The special coaching and streaming into better teams would eventually snowball the older kids’ talents far beyond the younger. There are plenty of non-sport examples too. A significant proportion of Oxbridge students are born September-December. Syed describes this as the “relative age effect”.

7. Foster self discipline

I can’t discuss future success without mentioning the Stanford marshmallow experiment. This was a series of studies on delayed gratification in the late 1960s/1970s led by psychologist Walter Mischel, a professor at Stanford University. In these studies, a child was offered a choice between one marshmallow provided immediately or two marshmallows if they waited for a short period (approximately 15 minutes) during which the tester left the room and then returned. In follow-up studies, the researchers found that children who were able to wait longer for the preferred rewards tended to have better life outcomes, as measured by SAT scores, educational achievement, body mass index, and many other life measures. I really fundamentally believe in the crucial role of self discipline in every aspect of your life. Short term pain for long term gain. This is a lesson children must learn. Syed talks about intrinsic motivation (see under 1); this is an essential precursor to success. This is what drives the ability to commit 10,000 hours to anything.

In thinking about this post, as I always do ponder my posts and the messages I’m disseminating, I realised that success for my children is totally irrelevant in comparison to their happiness. In most human beings, some form of “success” (achievement/fulfilment) is probably an essential precursor to happiness, but we all have differing opinions on what that means to us. I hope I can help my children find what it means to them and if they want to spend 10,000 hours dedicated to anything, I will support them in it.

I had a think through how I could integrate some marginal gains into our lives. The little practical steps that together might make a real difference. Most of us do this innately. For example, implementing routine changes like putting breakfast out the night before after experiencing morning rush, or allocating a single car key home after scrambling to find them. I constantly implement marginal gains into my nutrition and fitness; the concept sums up the EAT and MOVE sections of this blog as much as our own tagline ‘Be the best you can be’. In parenting, there is probably a lot more I could do. I should set alarms ten minutes earlier on spelling test days so that I’m not teaching my kids last minute cramming techniques in the car. I should insist on homework being done in a quiet place rather than at the kitchen bar where I oversee as I cook, I could read for five minutes more each day with each child, discuss sports kit with an expert, ask for more specific feedback from teachers so I can support learning… And then I realised that taken to extreme, this would be heading straight into Tiger Mother territory or Professional Mothering (both of which are so un-me, possibly paradoxically so, but just so un-me, some of the stories I hear in my demographic make me want to cry or scream). Plus, I am 99% just in survival mode. Aren’t we all? Just getting my three to their three different schools fed and on time in the right clean kit and with the right schoolbag and the homework done, play lines learnt, hair vaguely neat and shoes polished is pretty much all I can manage right now while managing a new business. Open question to Sir Dave Brailsford and Matthew Syed on behalf of all mothers in the world ever: how do you consider or integrate new marginal gains when you are 104% tired all the time? The concept is brilliant though and one I intend to use in every aspect of my life. Reading this book has dramatically affected the way I will parent, especially in terms of the language I will use to praise, criticise and inspire my children in order to inform their own behaviour and characteristics. I will try to foster resilience, a healthy work ethic, self-discipline, the ability to learn from mistakes and a belief in their own ability to succeed. It has also reinforced my commitment to these qualities in my own life. I hope you’ll read Black Box Thinking; you won’t regret it.